***Απαγορεύεται από το δίκαιο της Πνευμ. Ιδιοκτησίας η καθ΄οιονδήποτε τρόπο παράνομη χρήση/ιδιοποίηση του παρόντος, με βαρύτατες αστικές και ποινικές κυρώσεις για τον παραβάτη***

Greek literature abroad. In the context of exploring Greek literature’s introversion and extroversion, Literature.gr launches a series of interviews with translators. Our goal is to find out what exactly is happening abroad in relation to Greek literature; how widespread and well-accepted it is from foreign readers, what obstacles may impede its diffusion. Moreover, through these interviews and through the accumulated experience of the translators, we seek to trace the difficulties the latter face, the special features of the translation of Greek literature and the role of the translator in general.

Editing/ Interview: Aimilios Solomou

![]()

The first translation of modern Greek literature in Swedish was Demetrios Vikelas’ Loukis Laras in 1883. A translation of a series of folk songs had preceded in 1876. Since then and until 2007, 100 books have been translated – some of them from English or French – by 73 translators and were published in 43 publishing companies. Bo-Lennart Eklund, professor at the University of Gothenburg, presented the aforementioned data in Vasilis Vasileiadis’ book (ed.), “…familiar and foreign…” The Greek Literature in Other Languages[1] (pp. 265-277). As Eklund writes, “the interest of the Swedish publishing companies to issue translations of modern Greek literary works was primarily influenced by non-literary factors, mainly wars and violent political events”. It is important to note that the translations and publications of Greek literature were particularly prominent during the Greek 7-year dictatorship. Seferis is the most translated poet (25); next follow Cavafy (24), Elytis (16), K. Papakongos (16) who permanently lives in Sweden, Ritsos (12), Mikis Theodorakis (11), Vassilikos (9), Kazantzakis (9) and Myrivilis (6). Contrary to other countries, Kazantzakis’ primacy does not apply in Sweden (from 1946 and until his death in 1957 he was continuously a nominee for the Nobel Prize). Seferis’ preeminence is also due to the Nobel Prize of 1963, a fact that, as Elitis’ Nobel Prize, had a positive impact on the spreading of Greek literature internationally.

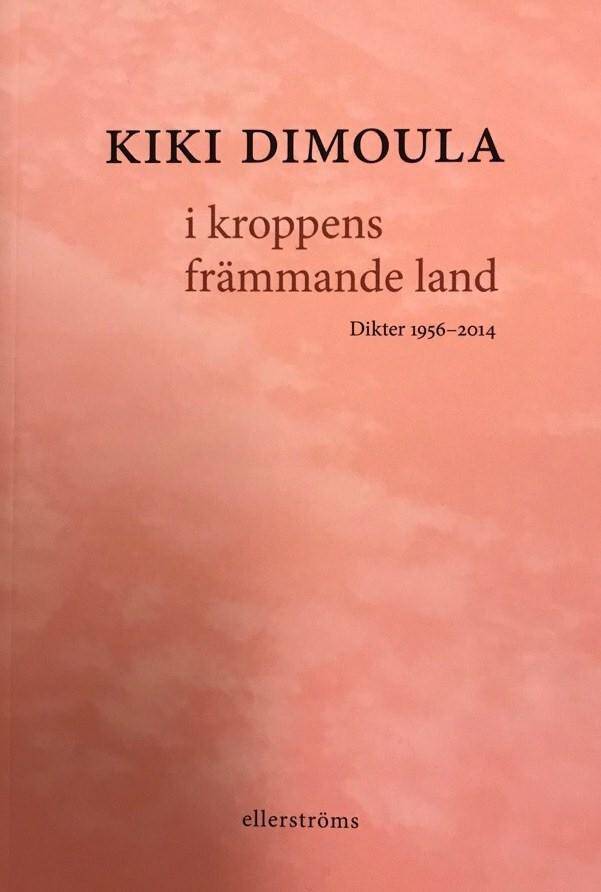

Jan Henrik Swahn and Rea Ann-Margaret Mellberg are a couple both in life and in translation. They have recently translated an anthology of Kiki Dimoula’s poems, I kroppens främmande land [2] (“The foreign space of the body”). In their interesting interview, they tell us about their involvement with translation, they delineate the image of Greek literature in Sweden and they explain why the prospects of translation are not very encouraging. They refer to institutions that promote or support Greek literature in Sweden such as the Swedish Arts Council (Kulturrådet), part of the Swedish Ministry of Culture, which financially supports Greek translations; they add (with a tone of regret as almost all the translators asked in this series of interviews) that the Greek state should assist Greek writers and the modern Greek literature for its further promotion abroad.

![]()

Under what circumstances did you decide to learn Greek and engage in the Greek language?

Swahn: My interest for the Greek language started in 1994 after a trip to Athens, Delphi and Rhodes, where young Swedish writers met with 6 Greek poets (Dimitra Christodoulou, Stratis Paschalis, Alexandra Plastira, Thanasis Chatzopoulos, Dimitris Chouliarakis and Haris Vlavianos). The initiative for the meeting was taken by the magazines 90TAL and Entefktirio from Stockholm and Thessaloniki respectively.

Why did you decide to undertake the translation of Greek literature in Swedish?

Swahn: I translate from many languages and I wanted to expand in the Greek language. I thought that translation is the best way.

Is Greek literature well-known in Sweden? Is there interest for new translations?

Swahn: During the years of the dictatorship (1967-1974) there was a lot of interest for Greek literature. Literary works by Elitis (Nobel 1979), Seferis (Nobel 1963), Ritsos, Leivaditis were translated thanks to Theodorakis; they were recognized and loved thanks to the musical compositions. Works of expatriate writers were also loved, such as those of Theodor Kallifatides and Andreas Nenedakis. We should add here that Nikos Kazantzakis’ and Constantine Cavafy’s works were translated and spread in the 1950s. After 1974 the interest for Greek literature weakened. We find scattered translations of new writers without any systematic organization. Writers search for Swedish publishers on their own and the discussions take place without the mediation of National Book Centers or other relevant institutions. The prospect for new translations is not particularly encouraging. For example, the anthology with Kiki Dimoulas’ poems (I kroppens främmande land, 2016) would not have been published if us two had not taken initiative.

Is the fact that the Swedish Academy awards the Nobel Prize an additional motive for Greek writers and publishers to translate Greek books in Swedish?

Swahn & Mellberg: Yes. Of course! Each year, many writers, more and less famous send us works with the hope that we will take care of their translation and publication in Swedish.

What is the profile of the Swedish audience that reads Greek literature?

Swahn & Mellberg: A small part of readers that are interested in Greek literature. Readers that are curious to learn something more about modern Greece; the financial crisis, modern politics, the everyday life.

Is it important for Swedish readers today to come in touch with Greek literature? Why?

Swahn & Mellberg: Yes, of course it is important. Greece is an indivisible part of Europe and in the united Europe in which we live, literature is the best guide for us to get to know people, places and lifestyles that regard us increasingly.

Based on your experience, what could impress the Swedish readers of a Greek book?

Swahn: Its literary quality, active narration and its commerciality in the country of origin; however, the latter is an uncertain criterion. For example, Judas Kissed Wonderfully had no success in Sweden.

Do Swedish people love literature in general?

Swahn: Swedish people are among the most reading inclined people in the world. It is mainly women that read reaching a percentage of about 90%. I should note that the biggest interest regards crime novels. We should not forget that Swedish writers are pioneers of this genre.

Bearing in mind that the (Greek literature) translator does not only translate the book, what other difficulties or problems might be faced from the choice of the book to its publication?

Swahn: In case I translate poets or authors to build an anthology, I come across the issue of choosing. If the proposal is made from Greece, it is not definite I have the liberty to select my writers without directions. The younger writers are usually in the shadow of the older generation and a lot of effort is needed for important fresh voices to be heard.

Are there institutions in Sweden that could be used for the promotion of Greek literature in Sweden (e.g. public libraries)?

Swahn & Mellberg: The Swedish Ministry of Culture: Swedish Art Council (Kulturrådet), continues funding translations of Greek works. The fund is decided by a commission which judges case by case. Regarding the promotion: book fairs; mainly the annual Gothenburg Book Fair. Some libraries, museums and expatriate entities organize readings and literary meetings with Greek and Swedish invited authors. For example, the presentation of Kiki Dimoula’s anthology took place at the Stockholm City Library (Stadsbiblioteket) with the participation of Stina Ekblad, the famous actress of the Royal Dramatic Theatre, Dramaten.

What would you suggest for improving the possibly problematic situation of the translation of Greek literature in Swedish?

Swahn: More writers should be presented in Sweden with the support of the Greek state. Not only the Swedish Ministry of Culture, but also other organizations, cover the expenses of selected writers who receive invitations to visit countries abroad and international book fairs. Greece should do the same.

On the other hand, is it true that the Greek financial crisis of the past years has been an interesting subject for the publishing companies abroad?

Swahn: No, it is not true. It is more plausible that Swedish writers benefit from the Greek crisis! For example, Kajsa Ekis Ekman wrote about the Greek financial crisis; and of course, the expatriate writer Alexandra Paschalidou who also writes in Swedish.

What are the peculiarities of translating from Greek to Swedish?

Swahn: The problems are mainly located in the big difference between north and south.

Is the translator a creator or a mediator between the writer and the reader?

Swahn: The translator is a creator!

What do you consider a good translation is and what could the handbook of a good translator be?

Swahn: A good translation does not strike one as a translation. The works that are translated from the native language are always better, since possible mistakes of an intermediate translator are avoided. The problem with not widely spoken languages, such as Greek, Swedish, or other languages is that usually there are not enough or available translators, so one resorts to translations they cannot control.

What important experience you have had through all these years translating Greek literature would you like to share with us? (maybe unknown incidents, or relationship – communication with the author etc.)

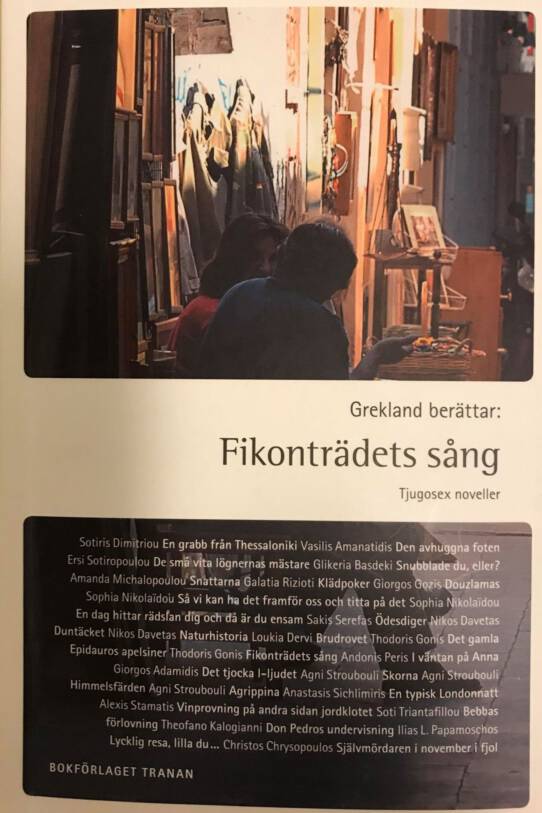

Swahn: The most interesting of my experiences was my choice to translate the narratives of the anthology of the new Greek authors Fikonträdets sång, (“The fig tree’s song”). On this occasion, I met and got related with most of the 25 authors. But Glikeria Basdeki I almost did not meet! They had given us a phone number of a place somewhere in Northern Greece; an elderly woman with the same name was answering the phone giving us confusing information. Supposing that she was a relative, I called multiple times with the hope that at some point the writer herself or somebody with whom I could communicate would answer. But unfortunately, nothing happened… A great disappointment; I gave up, since the elderly lady with her squeaky voice told me to stop disturbing her and to never call again! So, I included the narrative without permission. When the anthology was published, Basdeki learned I had translated her work! She happily got in touch with me and after some time we met in person! We are now friends and I particularly appreciate her literary work!

![]()

Video of the presentation of the translated Anthology of Kiki Dimoula

A small interview by Jan Henrik Swahn

Jan Henrik Swahn

He was born in 1959 in Lund. He grew up in Denmark, Copenhagen and in 1970 he moved to Malmö. Between 1982-1983 he was a scholar of the French state and he studied in Sorbonne IV. His first novel is called Jan kan stoppa ett hav [3] (“I can stop a sea”). Elven of his novels have been published until today, most of them by Bonniers. His works have been translated in Russian, Polish, Greek and Hebrew. He often writes for marginalized people (alcoholics, homeless, “crazy”, loner, elderly people – but without following the norms). He worked as an editor for Bonniers Litterära Magasin (BLM) (1997-99) and president of the Writers in Prison Committee, president of the Swedish PEN (1990 – 92) and member of the Administrative Board of the Swedish PEN (1988-93). In the past ten years he has been working with women that have been involved with drugs, prostitution, were homeless or were in any way abused. He is a well-known translator from, among other languages, Greek, Polish, French, Arabic and Danish. He has translated many books written by the Polish writer Olga Tokarezuk and the Greek Kiki Dimoula. Both are nominees for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

His novel Pengarna (“The Money”) won the TCO Prize (Swedish Central Organization of Salaried Employees) in 1997. In 2001 he received the most prestigious literary prize of the Göteborgs- Posten, the third biggest newspaper in Sweden. The same year, his novel Vandrarna (“The Wanderers”) was included in the very limited list of the August Prize, possibly the only very famous prize even abroad. In 2005 he was awarded the Sture Linnér Prize for the aforementioned book and for his translations of Greek poetry. In 2010 his book “The Wanderers” (published by Kedros) was in the short list of The Athens Prize of Literature. In 2017 he was awarded the Kulturhuset Stadsteater’s International Translators’ Prize for Olga Tokarczuk’s book Jacobsböckerna (“The Books of Jacob”). He is characterized as the only “Eastern European” author in Sweden. His literary works are the following: Jan kan stoppa ett hav (“I can stop a sea”) (1986), Den förbannade glädjen / (“The cursed joy”) (1987 – published in Greek in 2003), Kärlek och äventyr (“Love and adventures”) (1991), Husets alla färger (“All the house’s colors”) (1993), Pengarna (“The Money”) (1996), Tiggare (“Beggars”) (1999), Vandrarna (“The Wanderers”) (2001), Lingonkungen (“The king of lingonberries”) (2003), Drakkvinnan (“The Dragon Woman”) (2005), Manolis mopeder (“Manolis’ mopeds”) (2008), Mitt liv som roman (“My life as a novel”) (2011), Den som lever är fri (“He who lives is free”) (2015), NEKOB (“THE BOOK”) (2017).

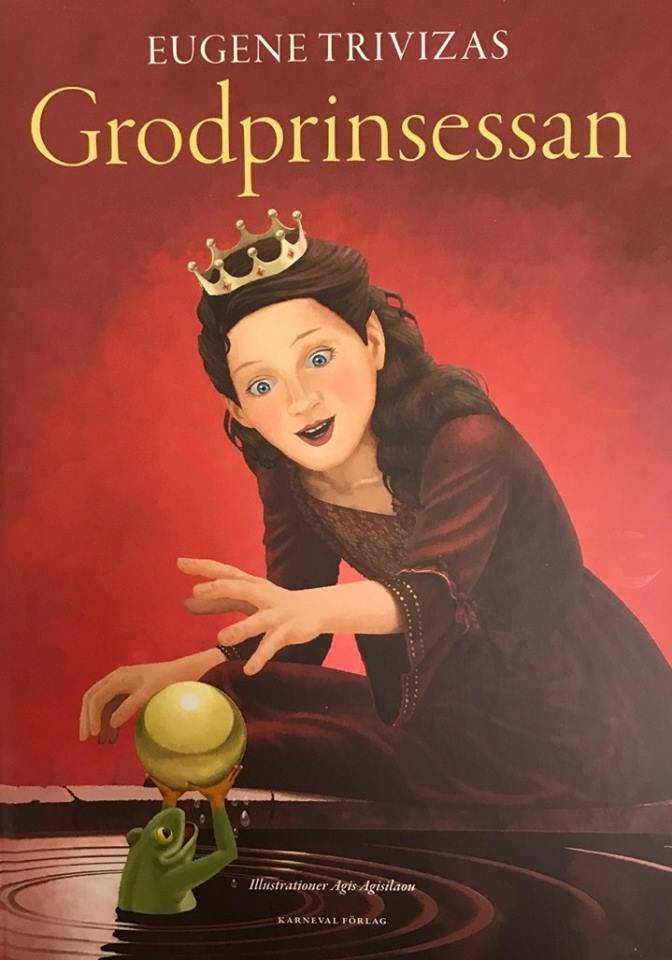

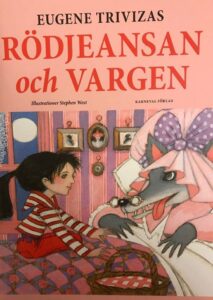

Translations: Maria Lainá – En snabb kyss (“A quick kiss”) (1999), Giannis Tzanetakis – Allt är väg (“Everything is a Road”), poems anthology (2002), Fikonträdets sång (“The fig tree’s song”), an anthology of Greek narratives (2008), Alexandros Papadiamantis – Mörderskan / The Murderess (2013), Eugene Trivizas – Rödjeansan och vargen (“The little girl with the red blue jeans and the wolf”), Grodprinsessan (“The frog princess”) (2018), Kiki Dimoula – I kroppens främmande land (“The foreign space of the body”), anthology, translation with Rea Ann-Margaret Mellberg (2016).

Rea Ann-Margaret Mellberg

She was born in Piraeus in 1951. She is the Minister Counsellor of Cultural Affairs at the Embassy of Greece in Stockholm. She has graduated from the Department of Classical Studies at Stockholm University; her scholarship awarded post-graduate studies were concluded at the same Department. She is also a Doctorate of Lund University (Doctorate Thesis Topic: Greek poets of the ‘70s). She worked as assistant professor of Modern Greek Studies at Stockholm and Uppsala Universities. She has translated: works from Strindberg, Ibsen, Dagerman, Almqvist, Swedenborg etc., Cavafy (in collaboration with the Swedish poet Magnus William-Olsson), Greek poets of the ‘70s generation and Cypriot poets. She has written theory texts and researches for Swedish and Greek authors and poets. She is a regular collaborator of the Greek literary magazines Γράμματα και Τέχνες (“Letters and Arts”) and Εντευκτήριο (“Enteftkirio”). She is a member of the Writers Union in Sweden and in Greece.

Among other things, she has translated, edited and presented in collaboration with Swedish musicians and Egyptian actors, texts about Hypatia (Alexandria 2002) and Cavafy (Alexandria 2007). Moreover, she has translated and presented texts about Dagerman (Athens, Nicosia, Kavala, Samos 2006).

Prizes and Scholarships: Nordenskjöldska, Swedenborg Scholarship 1990, Swedish Academy Translation Prize 1991, Friends of the Swedish Archaeological Institute Prize 1993, Swedish Writers’ Union Prize 1994, Scholarship for the translation of works of Strindberg – Swedish Writers’ Union 2010, Sture Linnér Prize 2017.

Translation from Greek: Alkmini Mouratidou

[1] Vasilis Vasileiadis (ed.), 2012, “…familiar and foreign…” The Greek Literature in Other Languages Center for the Greek Language, Thessaloniki, 2012

[2] Kiki Dimoula, I kroppens främmande land, trans. Rea Ann-Margaret Mellberg & Jan Henrik Swahn, ellerströms, Stockholm, 2016

[3] Jan Henrik Swahn, Jag Kan Stoppa ett Hav, Bonniers Publishing House, Stockholm, 1986.

![]()

Ακολουθήστε τo Literature.gr στο Google News και μάθετε πρώτοι όλα τα νέα για τον πολιτισμό και την επικαιρότητα από την Ελλάδα και τον Κόσμο.